During a recent (August, 1994) visit to Zambia I had the unexpected pleasure of meeting the finest rugby player Ireland has ever produced. Earlier in the year I thought I had scaled the summit of my sporting ambitions when I met the acknowledged doyen of sports journalists, Hugh McIlvanney. In these times when television, and the sporting press generally, hastily attribute qualities of greatness to obviously mediocre performers it was a refreshing experience to meet the genuine article. Nearly fifty years ago Dr. Jack Kyle left an indelible imprint on the world of rugby when his superbly improvised skills at out-half guided Ireland to its finest ever accomplishments (equalled sixty-one years later in Cardiff when Brian O’Driscoll led Ireland to a Grand Slam triumph in 2009). I met him in Chingola where he has been working as a surgeon for nearly thirty years at Nchanga South Hospital.

We had arranged to meet at his home in Oppenheimer Avenue and I arrived there with Fr. Tom Casey, SMA a few minutes early. I was told he was still at the Outpatients and while waiting in the sitting-room I was immediately struck by the realisation that it contained not a shred of evidence – no photos, no trophies, no caps – that its illustrious occupant was possibly the greatest rugby player that ever lived. When he entered a few minutes later he looked as nimble and lithe as he did nearly fifty years ago when he bamboozled the tightest defences. His entrance was marked with such ease and depth of courtesy that I instinctively knew why his grip on our imaginations (especially the imaginations of those like myself who had never seen him at his dazzling best in the flesh) has remained undiminished despite spending the last thirty years in a sporting wilderness. The essence of his greatness lies in a personality which has helped him soar to the ultimate heights of sporting achievement and still retain enough of the common touch to make anyone with whom he comes in contact feel important.

As a schoolboy (‘outstanding without being a prodigy’) he captained the Ulster Schools’ Cricket team and later played cricket and rugby for Queen’s. “My father used to say, Do you intend being a sportsman or a doctor? ‘Get your priorities right’ and I decided to give up cricket”. I had assumed that he must have been conscious from an early age of possessing a peculiar talent but my efforts at nudging him towards such an admission proved fruitless. “I remember as a schoolboy going to internationals at Ravenhill but it never once entered my head that one day I would be out there myself”.

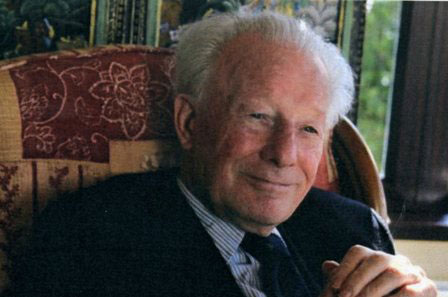

Dr Jack relaxes at his home in Bryansford, Newcaslte, Co Down on his return from Zambia.

Dr. Kyle first played for Ireland in 1945 against the British Army at Ravenhill in a game that also marked the debut of Karl Mullen, both only nineteen years old, who was later to captain Ireland in 1948 to the Triple Crown and Grand Slam. In 1946 he had played against France and England but didn’t play his first official international until 25th January, 1947 when he played in the losing game against France in Dublin. The next two games against England and Scotland were both won but they lost the Triple Crown to Wales in Swansea and were beaten by Australia in the last international of the season.

The 1948 season started brightly with victory over France in Paris and England at Twickenham. Kyle’s undoubted class was already emerging and he scored his first international try at Twickenham, a victory that was not to be repeated until 1964 in a game which marked the international debut of another rugby genius from NIFC, (Kyle’s club) Mike Gibson. Kyle again stamped his class on the game against Scotland with another magnificent try and Ireland had already won the Championship for the first time in thirteen years. The Triple Crown and Grand Slam decider took place against Wales at Ravenhill on 13th March, 1948 before a capacity crowd of 30,000. It was Ireland’s first Triple Crown victory in forty-nine years. The 1949 season brought further glory with another Championship and Triple Crown but not the Grand Slam. The 1949 season was also remarkable for the fact that it marked the first cap for a Catholic priest, Monsignor Tom Gavin of London Irish, (the only Catholic priest ever to have been capped at International level at centre in the 6-9 defeat to France and also in the 14-5 victory over England). Marnie Cunningham (Cork Constitution) who played for Ireland in 1955 and 1956 was ordained a priest after his International career was over.

Monsignor Tom Gavin [pictured during his rugby playing days] died on Christmas Day, 2009 at the age of 87. When he looked back on his two international appearances for Ireland, he gave credit, above all, to Jack Kyle, declaring: “He alone was worth the admission price”.

Monsignor Tom Gavin [pictured during his rugby playing days] died on Christmas Day, 2009 at the age of 87. When he looked back on his two international appearances for Ireland, he gave credit, above all, to Jack Kyle, declaring: “He alone was worth the admission price”.

In the summer of 1950 Kyle, still a student, was one of nine Irish men (Karl Mullen, George Norton, Mick Lane, Noel Henderson (his brother-in-law), Kyle, Tom Clifford, Jimmy Nelson, Bill McKay and Jim McCarthy) selected for the Lions Tour to Australia and New Zealand. They travelled by sea and the Tour lasted nearly seven months during which they played thirty games. Though the Series was lost 3-0 (with one match drawn) Jack still recalls the wonder of it all. “I learned much about rugby on the ship going out. Our P.T. instructor told us that the most important part of the Tour would be the lasting friendships we would make. I now know it was absolutely true. There were many wonderful characters in the squad, none more remarkable than the ebullient and voluble Tom Clifford (now deceased) from Young Munster whose party piece was O’Reilly’s Daughter’. I couldn’t sing but we all had to do something and I had a go at ‘My Uncle Dan McCann’ which I learnt specially for the Tour. Nowadays I’d give them a few verses of a Yeats poem”.

Jack Kyle’s international career ended in victory against Scotland at Lansdowne Road on 1st March, 1958 when he won his 46th cap, and he was then the most capped player in International rugby with 52 selections (46 for Ireland and 6 caps for the British and Irish Lions) then a world record. (Today Brian O’Driscoll with 133 caps for Ireland and 8 for the British and Irish Lions is the most capped International player). Jack Kyle finished his rugby career playing at full-back for NIFC Thirds before retiring from the game in 1961. The record books adequately convey the full significance of his achievements on the sporting field but they don’t even hint at his achievements in the medical field in the years since he hung up his boots.

After graduating as a doctor from Queen’s University he specialised in surgery before going to Indonesia where he spent two years (1962-1964) working for Standard Oil of New Jersey. Back in Ireland he spent a few years as a locum around Coleraine, Ballymoney and Derry before answering an advert in a Medical Journal in 1966 for a job in Chingola Mining hospital in Zambia. “As a child Africa didn’t seem nearly as exotic as South America or the Far East but I said I’d give it a go for a couple of years”. Major decisions had to be faced later when it was time for his two children – Caleb and Justine – to go to school. When he suggested to them that the whole family would move back to Belfast the children were horrified. As their father observed “We tend to forget that where we were brought up as children is where we consider home”. Eventually the Company sent them to Boarding School in Belfast (Caleb to Campbell College and Justine to Victoria and Methodist College) and they looked forward with relish to returning home to Zambia for the end-of-term holidays. Both of them love Africa and are delighted that their dad (‘I have no thoughts yet of retiring and I’ll keep going as long as I’m able’) has recently renewed his contract with the hospital.

When Jack arrived in Chingola in 1966 he was the only specialist in the hospital but with Zambian Independence under Kenneth Kaunda in 1964 the process of Zambianisation picked up pace and there are very few expatriates in the hospital today. “This place grows on you”, he admitted candidly, “and I still enjoy my work here tremendously”.

His contact with Rugby since he came to Zambia has been minimal. There are occasional invitations for speaking engagements among which he remembers with particular joy the Cork Constitution Centenary dinner in 1992.

As he reflects on the game he played with such distinction his mind focuses on the growing drift towards professionalism and he wonders, “How are we going to keep the money out of the hands of the people who produce the money – the players? The game’s administrators must stop having lots of individual millionaires. We must never forget that rugby is a team game. Chaps like me who flashed over for tries did so only because toiling in the mud were eight forwards whose names might never be mentioned”.

Jack Kyle’s assessment of his own ability clearly demonstrates that he can be passionate about rugby without losing his perspective about its place in relation to the deeper concerns of the heart. “Think of all the great players (the flying winger Freddie Moran springs to mind) who were unfortunate to be at their peak during the war years when there were no matches. I was extremely lucky to be born with a gift and fortunate to get the opportunity to use it”. I, too, considered myself very fortunate to have had the opportunity to meet a man of such modesty, humanity and natural warmth.

In conclusion I think it is appropriate that I borrow from ‘Markings’ some words of Dag Hammarskjöld, then United Nations Secretary-General who died in September, 1961 in a plane crash not far from Chingola. Dr. Jack Kyle is quite content these days to “be grateful as your deeds become less and less associated with your name, as your feet ever more lightly tread the earth”.

Published in the African Missionary magazine, Easter 1995, Fr Peter McCawille SMA