Readings: Deuteronomy 4:32-34, 39-40; Romans 8:14-17; Matthew 28:16-20

Theme: The great Mystery that defines and enfolds us.

Many of you will be familiar with the story of the Bishop testing a confirmation class on their knowledge of the Catholic faith. He asked one young boy: ‘What is the Blessed Trinity?’ Nervously, the boy blurted out his answer at breakneck speed: ‘Three persons ‘n one God’. Unsure of what the boy said, the Bishop exclaimed, ‘I don’t understand’, to which the boy replied: ‘You’re not suppos’d to; it’s a mystery. A mystery indeed! – the greatest mystery of our faith. It is also the central affirmation about the kind of God we believe in. As today’s gospel reminds us, we are baptized ‘in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit’ (Mt 28:19), and we begin and end our formal and informal prayers with this Trinitarian formula. The Trinity is not just a doctrine to be accepted in faith, or a formula to be recited in our liturgy. It is the great mystery that enfolds us and defines our deepest identity and destiny as God’s beloved children, as St Paul reminds us in our second reading today (Rom 8:14-17).

Sadly, as the noted German theologian, Karl Rahner, has remarked, for many Catholics the doctrine of the Trinity makes little impact on their lives. The language in which we were taught, from our earliest years, to think and speak of God is the main reason for this defect. God, we were told, was unchangeable being, all sufficient, perfect, and far removed from the imperfect world we inhabit. The relationship between God and the world was presented as a one-way relationship. God, we were taught, was not be affected by anything that happened in the world. He was the unmoved mover.

Fortunately, this remote and distant God is not the God revealed in the Bible. The God of the Bible is the birthing God of creation; the Spirit God drawing life out of chaos and enabling a universe of creatures to evolve and flourish; God, the Word incarnate, becoming one with us and redeeming and transforming human history. God’s closeness to us is seen supremely in the life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth. In Jesus we meet a God who goes in search of his lost child and rejoices when that child returns to the Father’s house. The parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15: 11-32) presents God as a loving Father who responds to human decisions and is affected by them. The God of Sacred Scripture is a passionate and compassionate God, capable of being deeply moved by the sufferings of his creatures. In the words of Pope Francis, the Bible reveal a ‘God of love who created the universe and generated a people, became flesh, died and rose for us, and, as the Holy Spirit, transforms everything and brings it to fullness’. This is the God who is Father, Son and Spirit.

Ultimately, the doctrine of the Trinity is as much about us as it is about God. It is about how God relates with us and how we are called and challenged to relate to one another. It is about what it means to be human persons created in the image of the One who is Love. Hence the Trinity is profoundly relevant to our everyday lives. To be human means to be like the God who created us; the God in whom we live and move and have our being; the God who chose to make his home among us through his Son; the God who lives within us through his Spirit. To become like this God of love means to live in relationships of love and respect, nor only with our fellow humans, but with all God’s creatures – all with whom we share the gift of life. In other words, we are called to participate fully in the Trinitarian communion of Father, Son and Spirit through our loving communion with one another and with all creation.

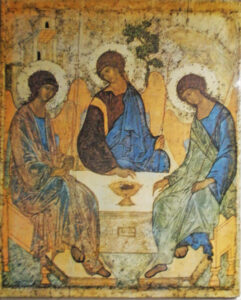

When words and ideas fail us utterly in our attempt to speak about the Trinity, great works of art can help us grasp something of its significance and relevance for us. A striking illustration of the revelatory power of great art is the beautiful Russian icon of the Trinity. Painted by Andrei Rublev in the early 15th century, it is based on the story of the three angels who visited Abraham at the oak of Mamre in Genesis 18:1-8. This icon presents three figures (representing the Trinity) sitting around a table. This extraordinary painting conveys a palpable aura of peace, harmony, mutual love and humility. At the front of the table, there is a vacant place, suggesting openness, hospitality and a welcome for the stranger. It signifies especially God’s invitation to us to take our place at the table of divine life and share in the communion of the three who are one. It is only at God’s table that we will find the nourishment for which our hearts hunger.

Here is a short poem on today’s solemnity of the Blessed Trinity from the pen of the Anglican poet, Malcolm Guite. It could serve as a communion reflection.

In the Beginning, not in time or space,

But in the quick before both space and time,

In Life, in Love, in co-inherent Grace,

In three in one and one in three, in rhyme,

In music, in the whole creation story,

In His own image, His imagination,

The Triune Poet makes us for His glory,

And makes us each the other’s inspiration.

He calls us out of darkness, chaos, chance,

To improvise a music of our own,

To sing the chord that calls us to the dance,

Three notes resounding from a single tone,

To sing the End in whom we all begin;

Our God beyond, beside us and within.

Michael McCabe

Click on the play button below to listen to an alternative homily from Fr Tom Casey SMA.

|

|