Readings: Ezekiel 37:12-14; Romans 8:8-11; John 11:1-45

Theme: ‘I am the resurrection and the life’ (Jn 11:25)

Today’s gospel reading from John recounts the familiar story of Jesus’ raising of Lazarus from death. This story includes the shortest sentence in the Bible: ‘Jesus wept’ (Jn 11: 25). These two words capture one of the most moving scenes in the life of Jesus, a scene in which he expresses the depth of his grief on the death of his friend, Lazarus. While John’s gospel is noted for its emphasis on the divinity of Jesus, it also highlights his humanity, his complete identification with us in all things, except sin. Jesus experienced the unspeakable grief that accompanies the death of a loved one, and so he wept – along with all those heartbroken at the death of Lazarus.

When a close relative or friend dies, something within us is broken beyond repair. Words fail us, and we are reduced to tears. Tears are the only language that can give expression to our grief, our acute sense of loss. Grief is the reverse side of the face of love, and our gospel reading today draws our attention to Jesus’ love for Lazarus. The message of Lazarus’ sisters to Jesus states ‘He whom you love is ill (Jn 11:3), and when the crowd see Jesus weeping, they remark, ‘See how he [Jesus] loved him [Lazarus]’ (Jn 11: 36). Love inevitably exposes the human heart to pain and sorrow. Jesus is the perfect example of a human heart constantly open to others in love and he fully embraced the intense pain and suffering that is part and parcel of all genuinely loving relationships.

The occasion of the death of Lazarus serves not only to draw our attention to the humanity of Jesus. It serves especially to manifest his divinity, to reveal him as the life-giving Word of God. Early on in his story, John tells us that, through the death of Lazarus, the Son of God will be glorified (cf. Jn 11:4). The raising of Lazarus from death is an illustration of the great truth about Jesus, proclaimed at the beginning of John’s Gospel: ‘All that came to be had life in him and that life was the light of people, a light that shines in the dark, a light that darkness could not overpower’ (Jn 1:4-5). It is also a climactic moment in the unfolding of Jesus’ life-giving mission, as affirmed in John 10:10: ‘I have come that they may have life and have it to the full’.

John narrates the story of the raising of Lazarus with great dramatic flair. It opens with Jesus being informed that his friend, Lazarus, is seriously ill. To our surprise, Jesus waits two more days before journeying to Bethany, where Lazarus and his sisters live. Bethany is close to Jerusalem, and Jesus and his disciples are quite aware of the danger that awaits him there. The Jewish leaders are plotting to capture and kill him. Thomas alludes to this danger when he says to his fellow disciples, ‘Let us also go, that we may die with him’ (Jn 11:16).

When Jesus arrives in Bethany, Martha and Mary rebuke him for not having come sooner. In welcoming Jesus, Martha says, ‘Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died’ (Jn 11:21). Later, when Mary comes from her house to meet Jesus, she falls at his feet and greets him with similar words (cf. Jn 11: 32). Jesus does not take umbrage at their implied rebuke, but makes the astonishing declaration, ‘I am the resurrection and the life’ (Jn 11:25) and leads them to express their faith in him. Martha responds in words that echo Peter’s profession of faith in Jesus: ‘I believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God’ (Jn 11:27).

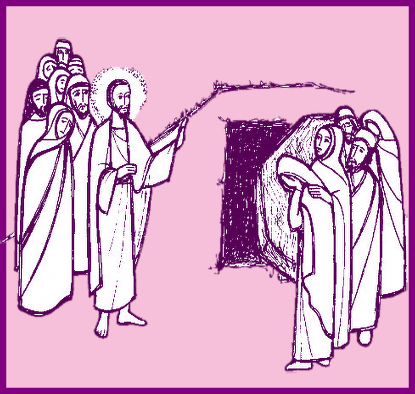

The climax of the story comes when Jesus is brought to the ‘cave’ where the body of Lazarus is entombed. Overriding Martha’s protests about the smell of death from a body already four days in the tomb, Jesus asks that the stone enclosing the tomb be removed. Then, following a prayer of thanksgiving to his Father, he cries out in a loud voice: ‘Lazarus, come out’ (Jn11:43). And, in laconic words that seem to contrast with the astonishing miracle they depict, John tells us that ‘The dead man came out, his feet and hands bound with strips of linen, and his face wrapped in a cloth’ (Jn 11:44). The story ends with Jesus turning to the awe-struck Jews around him and commanding them: ‘Unbind him, let him go free’ (Jn 11:44). The community is called upon to play its part in freeing Lazarus to emerge into the light of his new life.

When Vaclav Havel, the famous Czech dissident, and later first President of the Czech Republic, was released from jail after many years of imprisonment under a Communist regime, he stated that he ‘felt like Lazarus emerging from the tomb and awakening to new life’. He exhorted his fellow citizens to keep the flame of hope burning in their hearts. ‘Life without hope is empty, boring and useless,’ he said. ‘It is like being in a tomb. I do not know how I could have survived if I did not have hope in my heart. I am thankful to heaven for this gift. Hope is as big as life itself’. Let us continue to keep alive the gift of hope in our own lives as we profess our faith in the resurrection of the body and the life of the world to come

Michael McCabe SMA

To listen to an alternative Homily for this Sunday, from Fr Tom Casey of the SMA Media Centre, Ndola, Zambia please click on the play button below.

|

|